Posts Tagged Luke Andreski

A short conversation about honesty

Posted by Luke Andreski in Ethical consultancy, Ethical Intelligence, Ethics, Intelligent Ethics, Luke Andreski, Morality, Philosophy on December 9, 2019

1: An Introduction

Let’s talk about honesty.

Why is a good person honest?

Because a part of what goodness means, is to care about others.

If you care about other people, you’re honest with them.

Honesty shows respect.

2: Introducing someone who doesn’t like you

The degree to which someone lies to you is proportional to their disdain.

If they truly felt you were important they’d tell you the truth.

If you matter to them, they’ll know the truth matters to you.

But you don’t matter to a liar.

That’s why they’re happy to go on lying.

Narcissism, self-interest and indifference is the world liars occupy.

It’s the very air that they breathe.

3: The moral context

Honesty is a moral imperative.

Morality tells us to nurture those around us, to care for them.

You cannot nurture someone by lying to them.

In fact, the very opposite is true. Lies undermine and disempower. Lies weaken those who are lied to. That’s why the powerful lie. It reinforces their power.

Even ‘lying to protect’ patronises. It implies you know better than the person you’re lying to. It implies your superiority; their inferiority.

4: Equality

Yet morality tells us that in ourselves, as individuals, we are all equal.

Our actions, not our attributes, determine our moral worth.

We are equal whatever our ethnicity, origins, class or education.

Being honest with others recognises that equality.

It says, “You are as deserving of the truth as me.”

5: Facts = Power

Honesty empowers.

It places the full facts at your disposal and allows you to base your decisions and actions on these facts.

Facts make us strong.

Look at our technology, our incredible industrial society – all powered by fact.

Look at our engineering, our medicine, our science.

Look at the machines we build.

None of this would have been possible without facts, without honesty, without truth.

Engines don’t run on lies.

6: A flourishing human being

To be genuine with people, to be honest with them, is a signpost of morality.

Who would consider a liar a flourishing human being? Who would think them moral?

Who would want their closest friends to be liars? Or their partner? Or their child?

A person’s honesty is what we all admire, not their snake-in-the-grass deceits.

7: The truth will set you free

Being honest with others encourages honesty in return. It encourages an environment of clear-sightedness in which we can exercise our powers of thought and decision-making to the full.

Honesty is something to which we should all aspire.

Honesty fuels integrity.

Honesty sets us free.

See also the previous article in this series: A short conversation about lying.

For a detailed discussion of the parallel topics of propaganda and lies, see Ethical Intelligence by Luke Andreski:

www.amazon.co.uk/Ethical-Intelligence-Luke-Andreski/dp/179580579X

Twitter & Facebook: @EthicalRenewal

A short conversation about populism

Posted by Luke Andreski in Business Ethics, Ethical Intelligence, Ethics, Intelligent Ethics, Luke Andreski, Morality, Philosophy, Populism on December 1, 2019

1: An Introduction

Let’s talk about populism.

Populists pretend complex problems have simple answers. They like things so simple they become stupid. They like binary choices.

Populists demand you ‘take sides’. But isn’t it better not to take sides? Or at least not sides predefined by someone you may not wish to trust?

2: Divide and Rule

Polarisation is an authoritarian tool. It allows the manipulative to divide and rule.

But do we want to be divided, or ruled by immoral people?

Surely we have better things to think about, such as:

– Asserting our shared humanity

– Reversing environmental breakdown

– Creating a just and sustainable world?

3: Victimhood

Yet populists love division.

They like to polarise.

They like an enemy. If no enemy’s handy, they’ll make one.

They like to act the victim, no matter how rich or powerful or privileged they are.

But, by creating ‘an enemy’, victims are precisely what they tend to produce.

It’s one of the great ironies of modern politics: pretend victims, mostly powerful, privileged and wealthy, creating real victims: usually the powerless and the poor.

4: Base Instincts

Populism appeals to our worse instincts.

It appeals to emotions of hatred, resentment, rage, tribalism, ‘us’ and ‘them’.

Some instincts are good – but not all of them. They were developed over millions of years for a hunter gatherer existence…. but we are no longer hunter gatherers. Now we live in cities and inhabit virtual worlds. We exist within a complex web of connection, communication, interaction, participation.

In this complex modern world we need our better instincts to be brought into play:

- Caring

- Cooperation

- Empathy

- Creativity

- Compassion

Populism doesn’t care about caring. Compassion isn’t on its agenda.

5: Facts

Populism ignores facts. Predictably, therefore, populists dislike experts.

Experts know stuff. People who know stuff are a nuisance if you want to manipulate others rather than inform.

Populists, on the other hand, exaggerate, hype up, overblow, dissimulate and deceive.

For the rest of us this can be confusing. It distracts from the facts.

But for the populists it’s useful. It keeps them in the public eye. It all makes news.

6: Distraction

“Forget facts!” populists declare. “Just LOOK AT US.”

Into our eyes… Not around the eyes… Into our eyes.

Soon we are mesmerised by the show. We can’t see that they’ve got their hands on our voting cards or their spiteful little fingers scrabbling at the grey matter within our skulls.

While we’re distracted populists get on with achieving what they want to achieve.

7: Lies

Populists like to smear, slander, denigrate and accuse.

They love to lie. Why not? They’ll say anything to make themselves popular.

And the tribalism they encourage forgives lies. Being part of the tribe becomes more important than integrity. The tribalised forget their own morality. They forget the importance of being honest.

Of course, for the populists, the lie’s not the thing.

They don’t care about lying – in fact, they like it.

The lies not the thing… The objective’s the thing:

– Grubby ambition

– Ugly greed

– Pretending to serve others while serving only themselves.

Why let the truth interfere with objectives like these?

8: And more lies

And yet…. would you be happy if your brother, sister, father or mother were a liar?

Would you be keen to be known to be a liar yourself?

Is lying the example we want to set our children, our colleagues or our friends?

And, if not, we have to ask ourselves, “Is it truly acceptable – if we think about it for just a moment – for a President or a Prime Minister to be a liar?”

9: Morality

I’m sure it’s becoming clear from this discussion that populism is immoral.

Populists are serially dishonest, serially unreliable, serially self-serving, serially in it for number one.

They deny equality, kindness, our shared humanity, our compassionate human nature.

They create dissension, division, hatred, bloodshed, even war.

How can that possibly be moral?

How can it be moral to manipulate others rather than seek to explain – and, with honesty and accuracy, seek to persuade?

10: Resisting Populism

How do we resist populism?

At present it seems all-powerful – in the ascendant. It’s everywhere.

Populist leaders seem able to get away with anything…

One thing we can try is morality.

Not an old-fashioned, out-of-date, archaic morality – but a morality designed to tackle the issues of the 21st Century.

And the advantages of morality?

It’s hard to attack, slander or smear.

How can you condemn someone for being moral?

Morality is about caring for others.

How can you attack someone for caring for others?

Morality is about our shared humanity. Populism is about divide and rule.

11: A simple message

And morality’s message is simple:

- Morality 1st

- Integrity 1st

- Honesty 1st

And

- Make Humanity Great Again.

How can populism compete with that?

www.ethicalintelligence.org “The ethics of common sense”

Twitter & Facebook: @EthicalRenewal

For a detailed discussion of the parallel topic of propaganda, see Ethical Intelligence by Luke Andreski:

www.amazon.co.uk/Ethical-Intelligence-Luke-Andreski/dp/179580579X

The Practice of Ethics – A Leadership Guide

Posted by Luke Andreski in Business Ethics, Ethical consultancy, Ethical Intelligence, Ethics, HR, Intelligent Ethics, Morality, Philosophy on November 22, 2019

Morality – A critical success factor for business and society?

Luke Andreski – Graham Williams

There can be little doubt that we have reached a point in our history which is marked by profound ethical issues.

We face the acceleration of AI, an environmental crisis, the potential for future conflict over resource, probable large-scale migrations and an ascendancy of populist authoritarianism in politics across the world.

In parallel with this, another disturbing change has occurred. Morality has become unfashionable. It is no longer cool – and now carries with it connotations of ‘moralising’, of self-satisfaction or superiority, of being ‘moralistic’ or ‘preachy’. It’s as if, in the world of realpolitik and commerce, ethics no longer matter. Effectiveness and profit have taken morality’s place. ‘What’s in it for me?’ has become our guiding principle.

Yet this is a guiding principle which places our world in jeopardy. ‘What’s in it for me?’ cannot provide a solution to the major challenges which our businesses, our economies and even our species now face.

In addition to compassion, truth is at the heart of any moral code. If we cannot see our world clearly, if we are unable to separate reality from fake news or ideology, then how can we navigate our way towards personal, business or wider societal success? The reverse is also true. As our society drifts away from honesty, so it increasingly attacks it: a vicious circle we see all around us. It is now common to say, particularly of our politicians, that ‘everybody lies’. This then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Lying is normalised. We see this amongst some of the most prominent politicians of today’s world. A willingness to lie is no longer considered a quality which debars them from office. And the more they lie, the more they hate the truth. To quote George Orwell, “The further society drifts from the truth, the more it will hate those who speak it.” A wonderful example of this is seen in this interview with Michael Gove, the British politician campaigning for Brexit and the re-election of the Boris Johnson government:

https://www.channel4.com/news/michael-gove-interview-on-truth-lies-and-brexit.

It is also replicated in the many attacks we see from populist politicians on journalism and the press. Populism disdains experts and facts.

“To assert that everybody lies becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Lying is normalised.”

In collaboration with Graham Williams, a writer and consultant based in Cape Town, South Africa, I’ve been looking at how we can reassert the value of morality, honesty and compassion in a business context, and also for society as a whole. In a series of articles for Phase3 Consulting and HRZone I’ve argued for the value of ethics specifically within business. In my book Intelligent Ethics I expand this argument to society as a whole; and in his powerful work, The Virtuosa Organisation, Graham takes a similar approach.

There are so often situations in the marketplace where “business considerations” take precedence over ethical considerations – an either/or solution. Our contention is that this is a mistaken dichotomy. Business considerations (efficiency and profit) are in fact enhanced by adopting an ethical approach. Unethical practices exist in many toxic workplaces, including all forms of discrimination and exclusion, harassment, overt or unconscious prejudice and bullying – and tackling these can only benefit the performance, reputation and, ultimately, the profit of the business.

Leadership, training and coaching responses all too often fall into the ‘compliance’ and ‘rules’ category, when what is needed is:

- Development of an intrinsic ethical maturity and value base

- Encouragement of a learning, growth and mastery journey

- Nurturing of appropriate application in the context of the situations faced and their community impacts

To assist with this, we have drawn together a map of ethical best practice, outlining a set of cultural, process and human capital considerations for business leaders, a framework for:

- Providing a quick overview of the ethics landscape

- Moving from a rules-based to a values-based mind-set

- Guiding people how to behave positively and effectively, overcoming a bystander mentality

- Entrenching an understanding that ethics is an important bridge in aligning behaviours with core values

“Business considerations (efficiency and profit) are in fact enhanced by adopting an ethical approach.”

We hope you find this guide useful.

Luke Andreski

Graham Williams

November 2019

The Logic of Morality

Posted by Luke Andreski in Ethical consultancy, Ethical Intelligence, Ethics, Intelligent Ethics, Luke Andreski, Morality, Philosophy on August 2, 2019

I’ve made the case for the importance of morality to the functioning of modern society in my earlier WordPress article (here). However, it is also important to recognise that morality is not subject to relativism. It is not a pick and choose affair. Morality, whatever its originating cultural background, expects universality and consistency – and it operates according to its own internal logic.

In researching morality over the last two years, I have been able to identify a number of rules which invariably apply to or work within morality. I now document these as follows:

i. Morality requires a source of potent authority

Without this, any assertion of duty or moral obligation rings hollow. “Why? Why must I? Why ought I?” A potent authority behind the moral imperative is needed. Intelligent Ethics takes this from life itself – the source of all meaning, the essence of what we are.

ii. Morality applies to all human action

Morality encapsulates all other human activity. It is the primary and ultimate determinant of what we ought or ought not do. Everything sits within the moral context – even if, from within this context, it can then be assigned to the categories of morally insignificant or irrelevant.

iii. Morality is universal

In affirming a moral code you are also affirming that it is universal. Our core moral aims are applicable to all. It is the duty of all humans to be moral, wherever or whomever they are. It is their duty, and it is also their right.

iv. Morality necessitates and requires freedom

If you are not free you are unable to be moral. If you have no choice, if force or threat leave you no alternative, then your actions becomes amoral – devoid of moral content. Moral assessment and judgement then applies to whatever or whomever is coercing or controlling you. There is of course a sliding scale of freedom, and only the totally enslaved will be totally devoid of moral responsibility. If you have even a fraction of freedom then you are to that same degree responsible for your choices and your actions.

v. Morality cannot be enforced

Coercion and morality are inversely proportional: a person’s ability to be moral diminishes in direct proportion to the level of coercion used against them.

vi. The restriction of the freedom to be moral is a sin

If freedom is necessary for morality then the restriction of the freedom to be moral (or immoral) can only be a sin. It is therefore the duty of the ethical to morally enable others – to seek their freedom. To coerce or force others so that they are unable to make choices (even if this is the choice to be immoral) directly conflicts with the logic of morality – for as soon as a person is coerced to be moral they lose ownership of their actions and moral judgement ceases to apply to them. Explanation, education, encouragement and example are the tools of the ethical – not force.

vii. Morality requires an act of commitment

Because humans are free (see IE16 in my book Intelligent Ethics) we are free to be moral or immoral. If we wish to be moral then we must, of our own free will, commit ourselves to the authority of our morality. In doing this we accept that our personal whim and impulse are secondary to the direction and derivations of our moral code. We choose to accept the universality of the moral imperative and to live in accordance with our core moral aims. We choose to become moral beings.

viii. Morality requires consistency

A person cannot choose to be moral as and when it suits them, since this would effectively place their interests from one moment to the next above the authority of their morality – and thus denude their morality of authority or power. Morality without authority ceases to be morality (see IE15 in Intelligent Ethics and i, above). Further, on a purely practical level, a person who is unreliable and inconsistent is likely to be immoral in the sense that they cannot be trusted, particularly not in matters of importance or when it ‘comes to the crunch’.

ix. Morality requires honesty

If we are to know that a person is moral, and that we can trust them to act morally, then they must be honest. Dishonesty is not only immoral in itself (conflicting with our core moral aim to nurture others), it also undermines any claim by the dishonest upon being moral, having moral intentions or having acted morally. As with those who are inconsistent, you cannot trust the dishonest, particularly not in matters that matter.

x. Actions speak louder than words

Actions have greater moral weight than the words that explain or surround them or the protestations of those claiming to be moral.

xi. Actions speak louder than good intentions or motives

Actions have greater moral weight than the motives or intentions behind them. Motive and intention have a bearing in our evaluation of a person’s morality, but the person’s actions are the most important determinant of their moral worth.

xii. Intentions and motives speak louder than words

Accepting xi above, the intentions or motives which lead to an action nevertheless have greater moral weight than the words that excuse, explain or surround the action. Using your ethical intelligence to establish the intentions and motives of others is therefore essential in making moral decisions or determining a moral course.

xiii. Actions speak louder than inclinations

A person’s inclinations may be immoral, but if they are able to override these inclinations and their actions remain moral they can remain a moral person. For example, someone may have an inclination to exploit others which they cannot rid themselves of. However, if they succeed in suppressing that inclination and their actions remain moral, then their moral worth is the same as someone who has acted in a similarly moral way but has never had this inclination.

xiv. Words must always be measured by actions, and actions must always be assessed in relation to motive and intention

As x, xi, xii above.

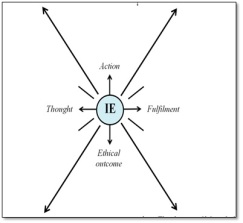

To demonstrate relationships between the following rules, I include them below as an image:

And continuing in my original format:

xxii. Past immorality must be redressed

As noted above (xx), the immoral can always become moral by undertaking moral action. Yet this does not mean previous immorality can be forgotten. The formerly immoral must still feel shame and regret for their immoral actions and seek to make reparation and restitution for any harm they have done. Only thus do they begin to ‘nurture others’ in accordance with our core moral aims (Intelligent Ethics, 1-xviii.i). Similarly, those who are aware of the past immorality of others may wish, for a period, to treat them with appropriate caution and care. This is pragmatic common sense, and pragmatism and common sense are also tools of the ethical.

xxiii. Moral wrongs are not eclipsed by greater moral wrongs

Because event a is more wicked and bad than event b this does not mean that event b can be discounted or lost from our moral calculations. All immorality must be challenged and addressed by the moral.

xxiv. Attributes are morally neutral

Ethnicity, colour, gender, sexual orientation, educational background or social status, birthplace, intelligence, talent, appearance and all the other attributes applicable to human beings are morally neutral. Your attributes do not determine your moral worth. Your moral worth is determined by the actions you take in furthering the human mission: in enabling your own flourishing; in enabling the flourishing of others, in enhancing the flourishing of humanity as a whole; in ensuring the flourishing of all life; and, to the extent that your capabilities and opportunities permit, in sharing life with the solar system and the stars.

xxv. Inaction equals action

If it is within your power to alter or facilitate the altering of a situation or sequence of events in the world around you, and you decide not to take advantage of this power (i.e. to do nothing), then this is morally equivalent to your exerting this power: the inaction is equal and equivalent to the action. Inaction may indeed be the moral course, but this must be a moral course consciously decided upon with full recognition of its impact. Similarly, to turn a blind eye to an immoral act or decision is as culpable as to knowingly witness and collude with that act or decision. This is because all human activity or inactivity sits within a moral context, and inactivity cannot exclude itself from this.

xxvi. Morality is inclusive

Morality excludes no one. Anyone, anywhere, at any time can be moral or become moral. They merely have to undertake moral action and desist from immoral action… and thus begin a moral life.

In morality there is no ‘us’ and ‘them’; there is only ‘all of us’, and we are all capable of being moral.

Luke Andreski

August 2019

http://www.ethicalintelligence.org

@EthicalRenewal

Ethical Intelligence and Intelligent Ethics are available from Amazon in paperback and ebook format:

UK:

Ethical Intelligence:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Ethical-Intelligence-Luke-Andreski/dp/179580579X

Intelligent Ethics:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Intelligent-Ethics-Luke-Andreski/dp/1794618732

US and International:

Ethical Intelligence:

http://www.amazon.com/Ethical-Intelligence-Luke-Andreski/dp/179580579X

Intelligent Ethics:

http://www.amazon.com/Intelligent-Ethics-Luke-Andreski/dp/1794618732

Freedom and Morality

Posted by Luke Andreski in Ethical Intelligence, Ethics, Intelligent Ethics, Luke Andreski, Morality, Philosophy on June 30, 2019

Freedom is an essential element of human flourishing. It is also a fundamental prerequisite for any form of moral code. If you are not free, then it is not your choice whether you are ethical or not. You have been intimidated or coerced into your actions. In so far as you have no choice, you have no responsibility. Your behaviour is restricted to doing as you are told under threat of pain, deprivation or death. You may choose to die rather than act immorally, but this is a hard decision to make. If you do not, if you live on, and if the scenario of enforcement is often repeated, then even this small degree of choice recedes: obedience becomes imprinted upon your psychology. You are truly a slave.

Resistance is harder still if those you love or who depend upon you suffer also for your acts of rebellion. Under such conditions, ethical choice is virtually eliminated. Survival and the minimisation of suffering for yourself and for those you love prevails. Moral decisions outside of these constraints become the least of your worries. It is therefore at the heart of ethics, and of anyone who lays claim to morality, that we commit to human freedom: that people are sufficiently sustained and liberated to be able to make moral choices, even to the extent that they can choose whether or not to be moral. Ethics without freedom is a hollow shell.

Yet we must ask how this reconciles with the deterministic view of human nature held by some philosophers and many scientists. What of our increasing understanding of the genetic and neurological causes of human behaviour and the ever-improving ability of sophisticated software to predict our actions and decisions?

There are two immediate answers to these questions. Firstly, a deterministic account of the universe which excludes all possibility of randomness, chance and choice is by no means set in stone. In fact, from a scientific perspective, our ability to prove determinism, to predict everything and to fully exclude all elements of randomness and spontaneity is receding rather than drawing closer. Chaos, complexity and quantum mechanics do not greatly contribute to the case for free will, but they do undermine a philosophy of brutalist determinism.

Secondly, even if human actions, in conjunction with the physical environment in which they operate, are in principle open to deterministic explanations, the scale and scope of these explanations will be so great that no human consciousness could comprehend them in their totality. We are embedded in our universe, looking at it from the inside out, and are therefore faced with a structural limitation upon how much of that external universe we can encapsulate within our minds, how much we can personally causally explain. There are limits to the data our brains and minds can process, and those limits are necessarily smaller than the totality of all there is to be known. This is true – and will always be true – even of our most powerful computers. In simple terms, the universe is bigger than our minds, and the entire picture is therefore both practically and in principle out of our reach. As a result, since we can’t know everything, our minds have no choice but to employ an assessment-and-decision-making process.

The argument becomes:

- As individuals we only have access to a finite amount of data.

- That data isn’t sufficient for us to be able to create causal explanations for all the events in our environments or to predict with any certainty the precise outcomes of our actions.

- Therefore it is a function of our minds to act as if we are free: to assess the data we are able to access, to make decisions based on the limited knowledge we have to hand, and to act accordingly.

In other words, our cognitive limitations require a decision-making mechanism whether or not the universe is causally determined. I cannot fully know the causal outcome of alternative actions, therefore I must make my best assessment and choose the action I am to take. Even in a rigidly deterministic universe our minds would be unable to operate as they do if it were not for this assessment-and-decision-making mechanism. Even if we could prove that our world is utterly deterministic and fundamentally predictable, the structure of our minds means that we have no option but to operate as if this were not so. In fact, this assess-and-decide ability is what freedom feels like. Allow us to use it and we feel free; take this power away from us and we feel enslaved.

This is also reflected in the fabric of the human world. Our societies operate on the assumption that free will exists. We are asked to make choices, or coerced by laws or punishments not to. Some behaviours are rewarded while others are discouraged, all on the basis of the choices we are presumed to have made. Most of our religions, all of our laws and all of our codes of behaviour assume we have choice. The way we live our everyday lives reflects this. Those of us who are not coerced or enslaved live as if we can make choices, as if we are free. We act and react to others as if they are free also: we judge them negatively or positively for the choices they make. Even in a fundamentally deterministic universe it is hard to see how society could operate differently – how society could function without assuming that those of us who are not coerced or enslaved are free. An assumption of free will appears to be a functional necessity of the social realm.

Evolutionarily, it can also be argued that our nervous systems and brains have evolved to provide precisely this: the ability to assess the state of the world around us, to register changes in our environment, and to permit an interrupt between immediate response and considered decision. If the world were fundamentally causal and predictable, why evolve this organ of assessment and choice? Why not stick to more autonomic and reactive lifeforms, possessed of a portfolio of built-in responses allowing for the various predictable events in a deterministic and predictable world?

This decision-making mechanism in semi- or fully sentient beings has demonstrable survival value and evolutionary worth. Why else would it be so prevalent in the more complex lifeforms on our planet?

The evolutionarily evolved interrupt between immediate response and considered decision sets us free. It privileges us with the ability to choose whether to obey our instincts or not; whether to gorge or fast; whether to strike out or to extend the hand of peace.

We are capable of choice:

Stone: Kicked by child

=> Reaction: stone skitters away along the road.

All causal. No interrupt.

Adult human: Kicked by child

=> Interrupt of cognition

=> Assessment (it’s only a child)

=> Decision:

Speak gently to child about inadvisability of kicking strangers

OR

Laugh indulgently

OR

Shout at child and reduce poor mite to tears.

The more we know about the adult, the child and the environment which they inhabit, the more we will be able to predict how the adult will behave. However, it is impossible that we will reach the position of always knowing enough to invariably predict all human actions or reactions – and the more complex the interaction between individuals and their environment the less reliable will be our predictions. Our minds are not built to hold in immediate awareness all the data we would need in order to predict everything. Our brains therefore must assess on the basis of limited information, and must make choices based on that assessment.

The nature of our minds and the limitations of our knowledge mean we must act as if we are free. This adoption of freedom – an ability to assess data and make decisions – is unavoidable, whether or not there are deeper, causal explanations for our behaviour which might in principle be found.

Our human interactions, our moral codes and our societies have evolved on this basis – upon the assumption of free will – and they, too, could not function without it.

Intelligent Ethics takes human freedom as both existential and axiomatic. Intelligent Ethics asserts our right to exercise this freedom, deriving our entitlement to freedom from our inherent equality as sentient beings.

Intelligent Ethics affirms our right to be free.

Luke Andreski

June 2019

Please also see:

“Intelligent Ethics” (recommended by former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams): www.amazon.co.uk/Intelligent-Ethics-Luke-Andreski/dp/1794618732

“Ethical Intelligence”: www.amazon.co.uk/Ethical-Intelligence-Luke-Andreski/dp/179580579X.

http://www.ethicalintelligence.org

@EthicalRenewal

Moral Authority

Posted by Luke Andreski in Ethical Intelligence, Ethics, Intelligent Ethics, Morality, Philosophy on June 2, 2019

In this article I discuss the nature of ethics and how a compelling source of authority is essential to any meaningful morality. I then look at how this moral authority is provided by Intelligent Ethics, as defined in my book of the same title.

The Is/Ought Divide

There is no formal logic which allows you to deduce what ought to be from what is. The facts of a and b only entail other facts – if they entail anything at all. The facts of a and b only entail that you ought to do c if another element is brought into the equation – a moral imperative, the element of moral authority. A ‘because’ is required.

If a is true and b is true then you ought to do c because…

Without the ‘because’, the facts of a and b may help you discover other facts, but they will not tell you what ought to be done with them or about them. An example might be,

Fact a: Kim is hungry

Fact b: José has food

What should Kim or José do? Or what should we do, who know these two facts? With these facts alone, standing in isolation, there is no means by which to determine what we should do. With these two facts and no additional moral imperative, we cannot deduce any action that ought to be taken.

We can perhaps deduce some other facts:

If Kim is hungry then Kim is a creature who requires nutrients for sustenance but something has prevented him or her from locating or ingesting such nutrients.

If José has food then José must have acquired this food in some way, perhaps through farming, perhaps through hunting or gathering, perhaps through barter or purchase.

If José has food then there is food to be had.

Should José share the food? Why?

The facts themselves cannot tell us why. You might shrug your shoulders and say, “Well, just because…” But that because merely assumes the presence of the missing ingredient. It smuggles in the moral imperative. It really says, “Because… it’s the right thing to do.” The meaning implicit in your words, if explicitly stated, would say, “Well, José should share the food because it is the right thing to do. If one person has food and another does not, then the person with food ought to share it.” And thus the ought is brought into play. Without the because and the ought the facts merely list the facts. Only the ought tells us what to do about those facts.

You are really saying, “Share that food, José, because it is the right thing to do.”

The authority of ‘Ought’

Having moved beyond the facts, you have now let us know that José ought to share his food. We have learned that it is ‘the right thing for José to do’…

Unfortunately this presents us with a new question: “Why is it the right thing to do? Why ought José share?”

Another “Just because…” isn’t enough.

Another “Just because…” really doesn’t carry sufficient weight. How will it convince anyone who thinks that José should keep his food? Maybe José has a hungry family. Maybe José needs his food for later… Why shouldn’t he keep it? Why should he share? Your “Just because…” offers little help. The person who disagrees might say, “Well, I think José ought to keep all his food for himself, just because…”

So the ought that we have introduced to tell us what to do about these facts itself needs something more. It needs a source of moral authority.

This source of authority cannot be, ‘Because I tell you so’, since someone else may tell us something different and claim it’s right because they tell us so. And it can’t be “Because I feel it in my heart,” or “Something deep within me tells me it is so,” or “An inner conviction convinces me of it,” because anyone else can experience those same things but derive a totally different ought. One person’s inner conviction may tell you the exact opposite of another’s…

In fact, ought isn’t truly ought if there’s nothing substantial to back it up, if it’s just a feeling, a conviction, an ‘insight’ or an intuition. None of these things adds the element of moral imperative to the facts of a and b. A different person’s feelings, convictions, insights or intuitions may come up with a totally different set of oughts, so where is your ought then? Without a source of potent moral authority your ought is just hot air.

To say, “Because it is your duty” merely begs the question, “Why is it my duty? You may feel it is your duty, but why should I feel the same?” Duty, too, requires a meaningful because.

Humans have tackled this problem by laying claim to an unlimited list of sources of command – the because behind the ought. ‘Human nature’, ‘alien instruction’, religious doctrine, ‘the historical imperative’, ‘economic necessity’, the words of ancient sages or modern cults, a ‘divine purpose’, an ‘intelligent design’, ‘the power of love’, a miscellany of ancient myths and texts…

And all of these attempts have been entirely valid in their purpose, since for ought to have any power or meaning there MUST be a because – and it must be a because that is able to convince us, to gain our commitment, our willingness to recognise its authority and to place it above random impulse or selfish whim.

Without a because there is no ought.

The because of Intelligent Ethics

Intelligent Ethics accepts the Is/Ought divide. It accepts that facts are not the basis for action; it is our interpretation of those facts and how they impact on what we wish or intend to do that determines how we act. It accepts that only ethics gives sense to human activity. If we do not have a moral code, then on what basis do we make our decisions? We cannot function let alone thrive without a compass to guide our behaviour, giving it meaning, consistency and purpose. Human society could not operate without an ought, and our ought is valueless without a because.

Intelligent Ethics accepts the Is/Ought divide. It offers a moral code defining what we ought to do, how we ought to behave. And it offers a because.

The because of Intelligent Ethics is as simple and self-evident as possible. The because of Intelligent Ethics requires no leap of faith, no interpretation by others, no hierarchy of prophets or priests, no epiphany or insight restricted to the privileged few.

In Intelligent Ethics Chapter 1, the Affirmation, I suggest that nothing has meaning if there is no life. Life alone has motive, drive, purpose, urgency, agency. For inorganic matter morality is meaningless. Morality is created by life and can only have meaning in the presence of life. The Affirmation of Intelligent Ethics says,

1-xiii There is no meaning without life.

1-xiv There is no purpose to human action if life ceases.

1-xv There is no morality, no duty, no ethics without life.

And concludes,

1-xvi Therefore the source of morality, duty, ethics is life.

But the fact that something is the source or origin of morality, a prerequisite for morality, does not in itself provide moral authority. We must take a further step:

1-xvii Therefore IE defines our first duty as the commitment to life itself.

This statement is simple and compelling, but it nevertheless demands a commitment on our part: to accept and affirm this definition and to place it at the very heart of our morality. Intelligent Ethics makes the divide between is and ought as narrow as possible, and a bridge is provided, but it is through an act of decision and commitment on our part that we cross this bridge. Intelligent Ethics defines our first duty as the commitment to life itself… and so must we.

The step is not a large one. Without life we have no meaning. Without life there is no morality, no duty, no ethics, no purpose, no point. Therefore nothing is more fundamental, more central to our existence, than life itself. There is no better or plainer source of meaning, point or purpose. It is to life that we must commit ourselves. It is in life that our duty lies. Make this affirmation, take this small step, accept this because, and you are gifted with a moral code. You have a compass for your life – and what better compass could there be? You have committed yourself to the very essence of what you are.

The necessity of Intelligent Ethics

Beyond this easily understood commitment a pragmatic case for Intelligent Ethics can also be made. At this point in human history, in the early years of the 21st Century, Intelligent Ethics is necessary.

Without shared and consistent codes of behaviour, enabling cooperation and understanding between communities, races and nations, humanity could never have come to live together in such large numbers, in such close proximity, with such success.

Yet a gradual failure of these shared ethics, a falling away of systems reliant on the thought pattern of belief, is leading to a crisis of culture and civilisation – a retreat to such basic moral codes as ‘You ought to do x, y or z simply because it benefits you.’ Or, which is similar, ‘You ought to do x, y or z or we will cause you suffering or loss.’ Neither of these – this bribe or this threat – are sufficient to sustain a diverse and thriving humanity in a flourishing biological world. They do not support the extended nature of moral authority, which transfers duty to those far beyond the reach of threats or bribes.

We have reached a point in our history where morality has become an essential survival trait. Without a renewal of morality modern civilisation, and perhaps even humanity as a species, may not survive – and our beautiful environment and all complex life upon Earth may join us in our fate.

The benevolence of Intelligent Ethics

The Affirmation of Intelligent Ethics offers three powerful assists for everyday life.

It provides a moral compass to guide our decisions and actions, one which can be shared with others: a basis for the reconciliation of disagreements and disputes; a framework for analysis, judgement and decision; a structure within which our actions make sense.

It provides a purpose for which to live – a mission both for ourselves as individuals and for humanity as a whole. Humans need purpose. More than that, we crave Not just as an essential element of social cohesion, but also as a source of transcendence of the self, as a grounds for fulfilment, as a measure of achievement, as a connection to others which reaches beyond our personal mortality and the mortality of our culture and times. Intelligent Ethics provides this. Our purpose is the human mission, the fulfilment of our core moral aims: the nurturing of others, the nurturing of ourselves, the nurturing of all life and the sharing of life with the empty reaches of the solar system and the stars.

It provides a code of behaviour which encourages kindness, understanding, compassion and love. It is our duty to nurture others, to nurture humanity and to nurture all life. This is part of what a commitment to life means. And these are elements of human nature which allow human society to work, succeed and flourish. They are elements of our nature which must be nurtured if society is to thrive.

The reward of ethical behaviour

There is an apparent selfishness in ethical behaviour which should not be used as an excuse for not behaving ethically. To be ethical sometimes offers rewards of personal fulfilment, contentment, a sense of well-being and even of pride. We might therefore ask, “Why are we being ethical? Is it simply to make us feel good about ourselves?”

The answer is, “It matters not.”

Any reward resulting from ethical behaviour is incidental. The moral imperative which governs our actions is independent of such rewards. Our Affirmation of Intelligent Ethics means we are duty-bound to behave ethically whether or not our behaviour rewards us with self-approval, satisfaction, fulfilment or happiness. Moral action is central to our commitment to life, to the Affirmation of Intelligent Ethics. Even if unrewarded, we must behave as our ethics dictates.

The psychological and emotional rewards that come to us as a result of our ethical behaviour are merely a result of human nature: a satisfaction gained from fulfilling our instinct to care for others, to take pleasure in their well-being, and to take pride and find fulfilment in doing good. These are evolutionarily valuable instincts which we will wish to nurture and encourage in an ethical world; they will assist our purpose and help us in furthering the human mission. Yet these could never provide the authority behind our moral acts. The authority is provided by our commitment to life, our affirmation of the human mission.

Not all human nature is unreservedly good or conducive to morality. Some of our instincts and appetites must be defanged or harnessed to good ends. They evolved for hunter-gatherers over millions of years; we are no longer hunter-gatherers. We must survive and live together in our billions by cooperative means. Apart from the energy we may gain through their redirection, many of our more assertive, aggressive or acquisitive traits are now counterproductive. But those of our instincts and traits which make being ethical a pleasure are instincts which we should encourage, instincts which will enable our species to flourish and our world to survive.

The transcendence of Intelligent Ethics

Intelligent Ethics sees life as the centre of all meaning. Life in its complexity, diversity, tenacity and beauty is something we must nurture and share to the fullest extent of our capabilities. Through the sensation of life, through our contribution to life, through the sense of life’s immanence, we can transcend ourselves and connect with a purpose far greater than the fleeting pursuits of everyday existence. Through nurturing others and connecting with all life we achieve a form of immortality. We connect with the very thing that creates meaning in our universe, with a force of enduring existence and purpose and worth. We connect with life. There is every reason to feel joy at this connection, to feel reverence, to feel a sense of wonder. Look in the mirror… Look at the smallest of the creatures around you… and you see manifestations of life which connect you to every other living entity upon this planet, which connects all of us to four billion years of evolution and existence – something of unutterable subtlety, complexity and beauty. Look around you. Look within you. What you see is life: transcendent and wonderful, complex yet elemental, multitudinous… yet each and every one of us unique.

Happiness, humour, irreverence and joy

To be ethical does not mean to be humourless or solemn. The ethical laugh, cry, joke or play as much as any other. The ethical can be emotional, exuberant, childishly happy, gleefully ecstatic or, if they so choose, dour, morose and glum. It is our choice who we choose to be or how we choose to express ourselves. Freedom is central to ethics (see Freedom and Free Will, below) and the ethically intelligent are free to be whomsoever they please. The ethical seek to nurture themselves and others. They help people thrive – and part of thriving is autonomy and being your own self. Humour, irreverence, flippancy, laughter and play are as much a part of our thriving as seriousness and solemnity. In fact, thriving humans in a thriving, ethical world might find that laughter comes more easily to their lips than it does in a world which idolises ruthless competition, endless consumption and disproportionate wealth.

A renewal of trust

Who can you trust in a world where success is rated more highly than morality? Where the manipulative impact of words is prioritised over their meaning? How can we renew our trust in our politicians, our corporations, our journalists after so much discord and conflict?

Morality offers a pathway to the renewal of trust.

If to be moral means to be committed to nurturing others, to nurturing humanity and to nurturing all life, then the person who is moral is by definition someone you can trust. A moral person’s motives are your well-being, your thriving and your fulfilment as well as their own.

We are disillusioned because those who work within our governments, our corporations and our media have forgotten to prioritise morality They have prioritised other things: profit, advancement, narcissistic self-esteem, power…

What must our governments, our corporations and our media do if they are to regain our trust?

The answer is profoundly simple. They must rediscover their morality. They must become moral.

A moral journalist is a journalist you can trust. A moral businesswoman is a woman you can trust. A moral congresswoman or parliamentarian is a congresswoman or parliamentarian you will find yourself able to trust. How can we know which of our leaders can be trusted? We can trust the ones who are moral. If none are moral, unseat them. Put someone who is moral in their place.

How to become ethical

There are no criteria of membership for Intelligent Ethics. You are ethical if your actions are ethical; you are not if they are not. This text provides guidance towards ethical action and assistance in understanding what being ethical means. A first step is to engage with, understand and affirm the core moral aims of Intelligent Ethics, dedicating and committing yourself to life as the source of moral authority. Then, with the core moral aims as your guide and the fourteen expressions of Intelligent Ethics as your templates for moral action, you are well positioned to be moral.

But positioning is not enough.

A person is only truly ethical when their thoughts, plans, intentions and words are translated into ethical action.

If you are to consider yourself a good person you must further the human mission through action. You must nurture others, you must nurture yourself, you must nurture humanity, you must nurture all life.

Ethical action is your uniform, your badge of honour. There is no other.

Luke Andreski

June 2019

Ethical Intelligence and Intelligent Ethics are available from Amazon in paperback and ebook format:

UK:

Ethical Intelligence:

www.amazon.co.uk/Ethical-Intelligence-Luke-Andreski/dp/179580579X

Intelligent Ethics:

www.amazon.co.uk/Intelligent-Ethics-Luke-Andreski/dp/1794618732

US and International:

Ethical Intelligence:

www.amazon.com/Ethical-Intelligence-Luke-Andreski/dp/179580579X

Intelligent Ethics:

www.amazon.com/Intelligent-Ethics-Luke-Andreski/dp/1794618732

What makes an excellent project manager?

Posted by Luke Andreski in HR, HR Implementations, Payroll, Payroll Implementations, PMBOK, PRINCE2, Project Management Consultancy, System implementations on November 12, 2013

I am exploring the topic of what makes an excellent project manager, potentially for an article on this blog.

Is it knowledge? Character? Experience?

Thoughts and suggestions at any level of detail and however factual or intuitive are welcome!

To participate in this discussion please join me on LinkedIn (http://www.linkedin.com/in/lukeandreski), email me (la[at]andreskisolutions[dot]com) or add your comments below.

Resourcing HR and Payroll Service and System Implementations

Posted by Luke Andreski in Consultancy, HR, HR Implementations, Payroll, Payroll Implementations, Project Management, Project Management Consultancy, System implementations on October 23, 2013

The Issue

The replacement of HR and Payroll systems or services is often commenced without a clear understanding of the resourcing required to ensure a successful project. Organisations undertaking such transitions focus primarily, at least at first, on the procurement aspects of the project. Where implementation resources are considered in detail, these usually comprise the resources to be provided by the supplier rather than those that will need to come from the purchasing organisation. The organisation may well ask the supplier, on the basis of their experience of these types of transition, to estimate the level of customer-side resource needed. However, it is likely that during the sales process the supplier will play down this requirement. It can be discouraging for buyers of systems or services to discover that not only must they finance a wide range of supplier consultancy activities but that significant internal resource costs will also be incurred.

In this article I discuss the customer-side resourcing needed in HR and Payroll system and service transitions. I also briefly touch on the types of resourcing which organisations should purchase from their supplier in terms of application consultancy, training, business intelligence consultancy, data migration consultancy and project management.

People And Skills

Implementations of systems and services inevitably require detailed decision-making, intensive configuration and close supervision of the supplier/client relationship. Even when organisations are outsourcing their HR or Payroll business processes, or transitioning between outsourced arrangements, customer-side involvement cannot and should not be avoided. Whatever the nature of the transition, a range of business-specific requirements will need to be met… and your supplier should not be the final arbiter as to whether or not this has been accurately and comprehensively achieved.

So, for HR and Payroll system or service transitions, what types of people and skills will an organisation need?

Whilst this is clearly subject to organisational size, business complexity and the degree of outsourcing involved, I attempt to broadly answer this question as follows.

Area Experts And Decision Makers

All system and service transitions will require the involvement of individuals who understand the business processes and system needs of the areas affected by the transition. For a transition to be successful it is crucial that these individuals have the seniority to make final decisions on system use or service provision without recourse to committee. It is also crucial that their allocation to the project is clearly defined and not simply slotted around a ‘day job’.

Examples of the type of experts needed by the project might be the payroll manager, an HR manager, the team leader of the Recruitment team, a Training manager and so on. I will touch on what this means in terms of FTE (full time equivalents) for each type of implementation later in this article.

Area Operators/Assistants

Transitions for in-house system use will require individuals with a working knowledge of the business processes in their area and with the skills to assimilate and apply any changes needed. They must have the aptitude to learn how to operate the new system and to share this knowledge with other users when required. HR and Payroll officers and Recruitment and Training administrators may be suitable for these roles.

It is also worth placing in these roles individuals who are positioned to continue working with the system or service after the transition has been completed, thus ensuring that the organisation benefits in the long term from the knowledge and experience gained during the transition.

Business Intelligence Experts

Business Intelligence is a crucial requirement from any HR and Payroll system or service, and transitions between systems or services must be managed closely to meet this need. Even within a fully outsourced arrangement the purchasing organisation may need to assign to the project staff who understand the organisation’s BI requirements:

– to ensure continuity of reporting;

– to liaise with the service provider;

– to confirm access to reporting; and

– to participate in report validation prior to go-live.

For in-house arrangements organisations will require staff who can administer the new reporting tool and write reports. Relying on the supplier for this can be inefficient and expensive. In smaller in-house scenarios the area expert may pick up these BI responsibilities, though this can significantly impact on implementation timescales.

System Users

Subject to the nature of the transition, future users of the system or service may need to be involved in the quality control and testing aspects of the project; and they will certainly need to be inducted into any changed business processes or system use. This requirement should be considered when preparing the business case for the transition and analysed closely during project initiation, in order to determine the likely impact on users and the amount of time they will need to set aside.

Technical Support / IT

The involvement of the organisation’s IT team will be required in any system and service transition, even if it is only to ensure access to an externally hosted database for data interrogation processes. In fully in-house arrangements, significant IT support will be needed during key stages of the transition to administer the set up and configuration of relevant servers (or to liaise with the supplier if these are hosted externally); to set up or liaise on comms; to provide desk top support to the project team; to liaise on installing the software and on subsequent software upgrades etc. Organisation size has a close correlation to the technical FTE required.

Project Management

With the obvious disclaimer on vested interests, I strongly recommend employing a customer-side project manager when transitioning between HR and Payroll systems or services. At one end of the spectrum this role might involve little more than managing and monitoring the service provider (a responsibility that can perhaps be assumed by one of the area experts); at the other extreme, for larger and more complex projects, it will necessitate a full time Project Managemer with Project Office back up, covering stakeholder management, project control and governance, project team management, supplier management and project communications. In the latter case it is not advisable to use supplier-provided project management since this creates a clear conflict of interest between project manager and project, i.e. the project objective of maximising quality and reducing costs vs. the supplier’s interest in maximising profit whilst minimising their costs (inclusive of project management time).

(Optional) Business Analysts

The suppliers of HR or Payroll systems and services are unlikely to emphasise the amount of business change implicit in the implementation of their product since this may deter potential customers. However, the business change implications for the organisation should be closely analysed, preferably in advance of the procurement, and the resultant workload assessed. In large scale projects the business analysts involved in this may also be deployed later on to facilitate the business change during the transition and to generate procedural documentation and guidelines on system use. In smaller projects the area experts or assistants may inherit this responsibility.

(Optional) Data Migration Specialists

Payroll and HR system and service transitions invariably require the migration of data from the old system to the new. For larger and more complex transitions, where data is sourced from multiple locations and significant mapping is required, it may be useful to deploy in-house data migration expertise if available.

(Optional) Testers

In smaller, in-house projects the Area Experts and Area Operators will undertake most of the testing activities, with participation where appropriate (e.g. during parallel running) from future system users. In larger projects, one or two individuals or even a team may be brought in to work specifically on testing and quality control.

(Optional) Trainers

Subject to the size, nature and complexity of the transition, trainers may need to be deployed to train system users.

Miscellaneous

Ad hoc involvement may be required from Audit, Finance, Communications, Employee Representation, Infrastructure, Property Services and so on. This will be determined by the nature and size of the organisation involved and should be identified during the initiation or planning stages of the project.

Resource Numbers (FTE)

So what are the resourcing levels that organisations will need during system or service transitions?

Clearly this must be definitively established through detailed analysis of the proposed changes and the business environment in which they are taking place. Nevertheless, to offer some initial guidelines, I hazard approximate “full time equivalents” below based on my experiences of these types of project and that of colleagues with whom I have worked closely.

In-House System Transitions For Large Or Complex Organisations (2,000 to 10,000 Employees)

| Resource | Numbers (FTE) | Comments |

| Area Experts And Decision Makers | 1 per area | If the organisation is undertaking an in-house Payroll and core HR implementation, with Recruitment, Training and Self Service to follow, then this would entail an initial ‘Area Expert’ FTE of 2 (these being HR and Payroll representatives at a management level). If Recruitment and Training are to be deployed in parallel, the FTE would rise to 3 or 4, subject to the scope of the later implementations. |

| Area Operators/Assistants | 1 – 2 per area | 1 FTE per area may be sufficient here, but this may need to be increased for larger and more complex transitions. |

| Business Intelligence Experts | 1 – 2 | If the organisation has a very large business intelligence requirement then up to two FTE may be required during the transition, to analyse the requirement, develop specific reports and configure report access and delivery. In moderately sized organisations 1 dedicated BI role is normally sufficient.An alternative approach is to train area experts or operators in the use of the Business Intelligence tool. This approach, in my view, is preferable, but it will add significantly to the FTE indicated in the boxes above, particularly in light of the training required. |

| System Users | Analysis required | System users may need to participate in:

– testing at different stages of the transition; – in discussions on current vs future system use; – in decision making; and – in parallel running and in attending training. The FTE utilised here is closely dependent on the approach taken to the project. |

| Technical Support / IT | 0.5 – 2 | Ad hoc IT support will be needed at various stages in the system transition: to administer the set up and configuration of relevant servers (or to liaise with the supplier if these are hosted externally); to set up or liaise on comms; to provide desk top support to the project team; to liaise on implementing the software or software upgrades; to maintain users and so on. Organisation size has a strong bearing on the technical FTE required. |

| Project Management | 1 | A dedicated project manager reporting directly to the organisation significantly improves the likelihood of a successful transition. Conversely, asking managers with other, primary responsibilities to assimilate this role inevitably compromises the management of the project.As noted above, it is also inadvisable to rely on supplier project managers as this introduces a clear conflict of interest: the supplier’s interest in maximising profit and minimising costs vs. the organisation’s interest in a successful project on time and in budget. |

| (Optional) Business Analysts | 1 – 2 | Business process re-engineering, if included in the transition, may well necessitate the involvement of business analysts. Business change can also negatively impact on the post-transition productivity of staff using the new system. |

| (Optional) Data Migration Specialists | 1 (occasional) | At specific points in the project life cycle 1 or more data migration experts may be needed to collect, collate, map, upload and test migrated data. This is normally supplemented by supplier consultancy. |

| (Optional) Testers | 1+ | Subject to the project life cycle and the size of the organisation 1 or more testers may be required for testing and quality control activities. This FTE will not be continuously required. |

| (Optional) Trainers | 1+ | Subject to the project life cycle and the size of the organisation 1 or more trainers may be required to train users in changed business processes and the use of the new system. This FTE will not be continuously required. |

| Miscellaneous | 0.5 | Involvement may be required from related teams, e.g. Finance, Audit, Properties and Communications. |

Note: Very large or complex organisations with tens of thousands of employees on very disparate payrolls will need to scale up the above estimates. Senior administrators or managers with experience of each type of payroll may need to join the project team. It is also the case that these types of transition respond well to increased resourcing – showing clear improvements in the quality of the implementation when good project staffing is provided. An example might be providing dedicated resource for project and system documentation, resulting in high quality procedural documentation being made available for current and future users of the system.

In-House System Transitions For Organisations of Moderate Size and Complexity (500 – 2,000 Employees)

| Resource | Numbers (FTE) | Comments |

| Area Experts And Decision Makers | 1 for HR, 1 for Payroll, 0.5 for other areas | Even moderately sized and reasonably straightforward Payroll and HR implementations tend to need one expert decision-maker for each area.Recruitment, Training, Self Service and other modules may well require less resource, or, if these are phased in after the HR/Payroll transition, the HR expert may move on to support the implementation of the smaller modules. |

| Area Operators/Assistants | 1 for HR, 1 for Payroll, 0.5 for other areas | Please see note above. |

| Business Intelligence Experts | 0.5 | It is difficult to predict the need for Business Intelligence skills in this scenario since this is very much subject to business need. The area experts may be able to meet this requirement but this will increase the FTE indicated above, particularly in light of the additional training entailed. |

| System Users | Analysis required | System users may need to participate in testing at different stages of the transition; in discussions on current vs future system use; in parallel running and in attending training. The FTE needed here will decrease with decreasing organisational complexity and size. |

| Technical Support / IT | 0.5 – 1 | |

| Project Management | 1 | |

| (Optional) Business Analysts | 1 | |

| (Optional) Data Migration Specialists | <1 | At specific points in the project life cycle data migration tasks will need to be undertaken. This work may be inherited by the area experts. |

| (Optional) Testers | 1 – 2 | Subject to project size and complexity. It is in fact more likely that the Area Experts, Area Operators and future users will undertake this activity. |

| (Optional) Trainers | 1 | |

| Miscellaneous | 0.5 – 1 |

In-House System Transitions For Smaller Organisations (Less Than 500 Employees)

| Resource | Numbers (FTE) | Comments |

| Area Experts And Decision Makers | 1 HR, 1 Payroll | System transitions for smaller organisations can be very demanding, since in-house resource is often difficult to find and often one or two individuals combine many of the roles indicated in this table. |

| Area Operators/Assistants | 0 – 1 per area | As a minimum even small organisations will benefit from 1 HR FTE and 1 Payroll FTE to see through a successful transition. In this scenario the Area Expert and the Area Operator is often the same person. A less efficient option is to have multiple part-time contributors. |

| Business Intelligence Experts | < 0.5 | In-house Business Intelligence expertise is critical to a successful project – but it may be the case with small organisations that this must be provided by the HR or Payroll area expert or by the supplier. |

| System Users | Analysis required | See comments above. |

| Technical Support / IT | 0.5 | Technical support cannot be avoided… but the requirement will be ad hoc rather than continuous. |

| Project Management | 0 | For system transitions in small organisations the project management is likely to be provided by one of the area experts or by a manager on a part-time basis. In either scenario, it is advisable that the individual picking up this responsibility researches the typical life cycle of these kinds of project. (A modest starting point might be my article Getting System Implementations Right.) Ideally an experienced project manager will be brought in, possibly on a part time basis. |

| (Optional) Business Analysts | 0 | Undertaken by the area experts. |

| (Optional) Data Migration Specialists | 0 | Undertaken by the area experts. |

| (Optional) Testers | 0 | Undertaken by the area experts and operators. |

| (Optional) Trainers | 0 | Undertaken by the area experts. |

| Miscellaneous | Ad hoc | Undertaken by the area experts. |

Note: The relationship between organisation size/complexity and the resource required for system transitions is not directly proportional. A minimum amount of resource will be needed for even fairly small organisations. If insufficient resource is allocated there will be a significant risk of project failure or of overloading the individuals assigned to the project.

System Implementations With Partial Outsourcing

To determine the resources organisations will need where partial outsourcing is planned, please see the estimates in the tables above. For each area being outsourced the Area Expert FTE can be reduced by 50-75% and the Area Assistants to 0%, since much of this work will be picked up by the service provider. The Area Expert FTE cannot be reduced to 0%, however, because in-house expertise will still be required to monitor the setup, testing and outputs of the service being provided.

Transitions To or Between Fully Outsourced Services

| Resource | Numbers (FTE) | Comments |

| Area Experts And Decision Makers | 0.25 – 0.5 per area | As noted above, the Area Expert FTE cannot be reduced to 0% since area expertise will be needed to make decisions on the service configuration and to monitor the performance of the supplier and the service. |

| Business Intelligence Experts | 0 – 2 | If the outsourced provider maintains a database which the organisation’s staff must access for their reporting and data needs, then business intelligence expertise may well be required during the transition to set up or refresh the reports to be used. |

| Technical Support / IT | 0.5 – 1 | Ad hoc IT support may be needed for desktop and comms if the organisation’s staff access an externally hosted database for their reporting and data needs. |

| Project Management | 0.25 – 0.5 | Some element of supplier and resource administration will be required even for fully outsourced transitions. |

| Miscellaneous | 0 – 0.25 | Contributory work may be required from teams such as Finance, Audit, Communications etc. |

The above table indicates the resourcing needed for transitions in outsourced arrangements for small to fairly large organisations. Larger national and multinational organisations with employee numbers in the tens of thousands will need to scale these up accordingly.

Implementation Services Provided By The Supplier

As part of the procurement of new HR and Payroll systems or services, organisations will need to buy help and support for their implementation or transition. For organisations taking in-house solutions, the suppliers can be expected to provide:

– Supplier-side project management, to oversee the day to day relationship with their customer and the timely delivery of the purchased products or services;

– Application consultancy, to lead the customer’s project team through the setup required to implement and use the new system;

– Business Intelligence consultancy, to advise on reporting tool configuration and potentially produce the more complex reports needed for go-live;

– Data Migration consultancy, to facilitate migration into the new system;

– Tech consultancy as determined by the proposed hardware, comms and database configuration;

– Bespoke software development; and

– Training in all areas of the new system and in the use of the reporting tool.

The numbers of days purchased for each of the above types of consultancy will be subject to analysis, negotiation and the supplier’s recommendations. However, it is important for organisations to emphasise during the procurement and within the resultant contract that these recommendations should be reasonably binding and that a stream of change controls relating to work that the supplier should have been able to foresee will be unwelcome.

Areas which are frequently underplayed in system and service transitions are the amount of training required; the amount of data migration consultancy which should be purchased; and the amount of bespoke development needed. Examples from a recent project I worked on were the omission of a Finance interface from a Payroll implementation contract, which then had to be separately purchased at considerable extra cost; and the failure to recommend data migration consultancy to cover fairly obvious data such as post and hierarchy information.

Conclusion

In summary, HR and Payroll system or service transitions are almost always more resource intensive than organisations expect. This is partly because organisations tend towards optimism when it comes to using existing staff, and partly because system and service providers tend to emphasise the direct rather than indirect costs arising from transitions. To avoid surprises it is therefore useful, when preparing the business case for such transitions, to include a detailed analysis of this potential area of cost. The resourcing guidelines above will, I hope, offer a useful starting position for organisations embarking upon this exercise.

November 2013

Luke Andreski PMI PMP

Project Management Services

http://www.linkedin.com/in/lukeandreski

https://andreskiprojectmanagement.wordpress.com/

With thanks to Emily Roach of Approach BI Ltd for the addition of ‘Testing’ resource to the above discussion.

© 2013 Luke Andreski. All rights reserved.

Managing Your Software Or Services Supplier

Posted by Luke Andreski in Consultancy, ERP, HR, HR Implementations, Payroll, Payroll Implementations, PMBOK, Project Management, Project Management Consultancy, Supplier Management on June 25, 2013

A reputable supplier

You are transitioning between services or systems. You have a good contract. You have a strong project team. You have selected a reputable supplier. What could go wrong?

Almost by definition all transitions are subject to increased risk. This may be due to lack of familiarity with the new supplier and their service or software; it may result from ambitious timescales; or it may arise from resource limitations and budget constraints. Whatever the reason, it is certainly the case that something can and probably will go wrong: with the deliverables, with the delivery, with the relationship between you and your supplier.

In Getting System Implementations Right and Prerequisites For successful HR and Payroll Implementations I discuss strategies to minimise the risks within organisations for transitions of this kind. In this article I look at ways to address the risks which arise specifically from your supplier and your relationship with them.

Common weaknesses

As a first step towards the management of your supplier it is important to identify their potential weaknesses. During the sales process you should ask your supplier to assess their own weaknesses, both past and future, and how they intend to address these in relation to any arrangement with yourselves. An independent assessment of your supplier’s weaknesses should also be undertaken through research, trawling the internet and speaking with existing customers. Weaknesses you are likely to find will include:

- Diminishing commitment once the sale is agreed and the contract signed

- Poor relationship management

- Erratic communication, both internally and with their customers

- Inadequate resourcing, in terms of availability and skills

- Failings in the product or service delivered

- Insufficient implementation support

- Tardy operational support

- An unhelpful corporate ethos

I will discuss these, and the measures you can take to reduce their likelihood and impact, below.

Perfection itself?

In seeking to manage your supplier it may not be weaknesses solely on their part which need to be identified and addressed. No organisation is perfect, and you will need to mitigate against weaknesses of your own. Examples might be:

- Insufficient resourcing of supplier management

- Unfocussed communications with your supplier

- Insufficient clarity of purpose

- Inconsistency in negotiating issue resolutions

- Lack of forcefulness

Mitigating risk

Once you have identified the potential risks inherent in your relationship with your supplier or in their delivery of product or service, you will need to put in place actions or plans to mitigate against these risks.

Supplier commitment and motivation

How can you ensure the continuing commitment of your supplier after the sale has been agreed? Once your contract with your supplier is signed, the charming and effective sales wing of your supplier’s organisation will hand you over, as a new project, to their delivery team. In many organisations what happens next will have little impact on the staff with whom you were to that point involved. The sales team will turn their attention to new prospects and new sales, and your new contacts will have a less compelling (i.e. no longer commission driven) motivation to meet your needs.